Nakimu Caves

- by Michael Morris, Parks Canada

- January 23, 2002

Nakimu is a native Shuswap word for “grumbling spirits”, a name inspired by the sound of the throbbing cascades of Cougar Brook as it disappears from a subalpine forest into a series of sink holes in Glacier National Park.

Water flowing through a soluble band of limestone sandwiched between harder rock types has carved an irregular system of caverns, narrow passages, drop-offs and other strange rock formations underground. Nakimu Caves, a six kilometre maze of interconnecting passageways, provides a rare opportunity for exploration into a dark underworld. Visiting the cave is an inner journey in more ways than one.

First explored by Charles Deutschmann in 1904, the caves were part of the Glacier House hotel era where early park visitors were escorted by Deutschmann, working as the first ever interpretive guide hired by a Canadian national park. A carriage road up Cougar Valley and a teahouse near the cave entrance were well used through the 1920s, but visitation declined with the closure of Glacier House.

The rotten, decrepit remains of staircases from Deutschmann’s time were removed in recent years by work parties comprised of local cavers and park staff. Today Nakimu Caves are protected as a wilderness with the intention of keeping them as natural as possible.

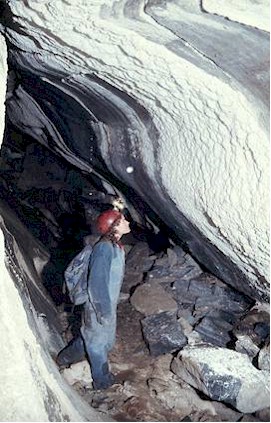

Moonmilk in the Nakimu Caves

Parks Canada photo

Access to all caves in national parks is restricted to preserve delicate cave features and to protect unprepared visitors from a dangerous place. Cavers entering Nakimu must be able to navigate in a complex system, to crawl through constricted places, and negotiate slippery surfaces above holes of unknown depths. A permit to enter the caves is limited to knowledgeable cavers, who must apply to the Park Superintendent.

In summer, passages near where the brook rumbles through reverberate with the sound of crashing water, reminding us that this cave is still in the process of formation. Blocks of rock still fall from the ceiling and lower passages can fill with unpredictably with water. In winter, stream flow is greatly reduced and most of the seeping water is frozen, often in bizarre arrangements. Cave temperature is only slightly cooler in winter than in summer, but in contrast to above-ground winter conditions, a winter visitor finds the cave relatively warm.

Moonmilk, a bacteria-instigated precipitate of calcium carbonate, is one of the cave’s remarkable features. It coats some of the cave walls with a pale ooze resembling soft cauliflower. It too easily bears the imprint of curious hands not intending to leave a permanent record. Marks in the moonmilk made by visitors from Deutschmann’s time have yet to fully recover.

Getting to the cave via Balu Valley is a 7 kilometre journey though avalanche terrain in winter and grizzly habitat in summer. The use of Cougar Valley for summer access was discontinued in 1996 due to bears. Subsequent radio-collar results show this area is prime habitat for female grizzlies. However, this route can be used in winter when it is not closed for avalanche control. The slopes of Cougar Valley are part of the area controlled by artillery to protect the Trans Canada Highway.

Helmets, protective clothing and specialized caving equipment are required here. Camping is permitted for cavers at Balu Pass. Caving advice and information regarding snow conditions or bears is available from Park Wardens. Prior registration for caving is mandatory.

In the cave I marvel at my guide’s ability to find the route. There are few reference points to indicate which way is up. For a few moments we extinguish our lights to experience utter blackness. We cease our prattle and listen to the rumble of the creek in some adjacent passage. At the end of our visit we climb out to emerge from hours spent in dark confines. Back on the surface, I’m a bit dazed by the intense colours, the complex smells, and the presence of other living things. The zone on the surface of the planet where life exists seems so thin.