Mountain goat census in Purcell Range

- by Michael Morris, Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks

- April 10, 2002

“It doesn’t seem possible that a mammal as large as a mountain goat could find enough to eat in such a place,” I think to myself as I look across from the helicopter window to steep, snow covered slopes.

I’m recording goat sightings from two other observers as part of a recent federal / provincial mountain goat population survey along both sides of the eastern boundary of Glacier National Park. The survey area includes Canyon, Grizzly, and Quartz creeks, and the many pocket valleys of the Dogtooth Range and Heather Mountain. Though we searched an equal amount of territory inside and outside the park, 33 of the 40 goats we find are in the park.

Typical mountain goat winter habitat, Parks Canada photo

Despite the steepness of the terrain where we find the goats, the snow cover appears to blanket the ground completely. Most of the goats we find are near motionless, sheltering at the base of small cliffs in the alpine. Tucking themselves under small overhangs affords some protection from avalanches. But what is there to eat, I wonder?

Living in such difficult terrain is the mountain goat’s survival strategy, a place where predators such as wolves and cougars can’t make a living. Should a threat appear, they’re prepared to clamber to the relative safety of small ledges. They manage this with small, pointed hooves with a roughed pad that provide good grip. But their small feet and short legs are not well suited for moving through deep snow. To conserve energy they prefer to stay put. The goats we spot hardly move at all. Do they feel secure, or are they too hungry to spend the energy?

To minimize disturbance to mountain goats, a population survey conducted by helicopter avoids getting close and follows the protocol of beginning low in the valley, climbing 200 vertical feet with each subsequent transect. By approaching from below the goats have time to adjust to the intrusion. Approaching from above may too closely resemble the predatory behavior of golden eagles, something mountain goat kids should dread.

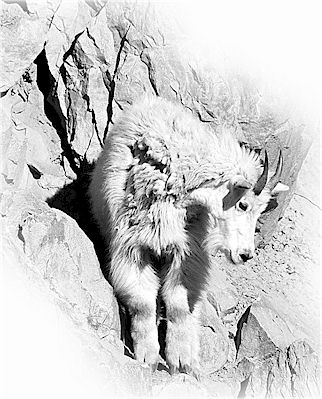

Mountain Goat, Parks Canada photo

White animals that stand still on snow are difficult to survey accurately. But flying by them too close or too often could spook them to move into even steeper and more dangerous precipices. Monitoring programs such as this must be conducted with due care of the subject.

Knowing if wildlife populations are increasing, decreasing or stable is central to our understanding of their future. The results need to be scientifically valid to be accepted let alone acted upon. But our interpretation of ecological trends will always be tempered by the inherent uncertainties of what we don’t know.

Despite the pilot’s best efforts, the repeated swinging back and forth in the helicopter eventually turns me green with nausea, to the point where it becomes difficult for me to fill in the numbers on the survey sheet. After a few hours of this we land for fuel in Rogers Pass. I exit the helicopter in desperate need of walk in the cold air.